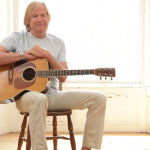

JUSTIN TALKS WITH 97.1, THE RIVER

Moody Blues frontman Justin Hayward recorded his new CD/DVD, “Sprits…Live, Live at The Buckhead Theater, Atlanta” here last year, and it is now available. Kaedy Kiely spoke with him recently, and he says he will be back at the Buckhead Theater this October! listen here [7:42]

Past Interviews:

Justin Hayward of the Moody Blues has a sold out concert at the Buckhead Theater on August 17th. Kaedy interviewed him recently, listen here.

Although they’re best known today for their lush, lyrically and musically profound (some would say bombastic) psychedelic-era albums, the Moody Blues started out as one of the better R&B-based combos of the British Invasion. The group’s history began in Birmingham, England with Ray Thomas (harmonica, vocals) and Mike Pinder (keyboards, vocals), who had played together in El Riot & the Rebels and the Krew Cats. They began recruiting members of some of the best rival groups working in Birmingham, including Denny Laine (vocals, guitar), Graeme Edge (drums), and Clint Warwick (bass, vocals).

The Moody Blues, as they came to be known, made their debut in Birmingham in May of 1964, and quickly earned the notice and later the services of manager Tony Secunda. A major tour was quickly booked, and the band landed an engagement at the Marquee Club, which resulted in a contract with England’s Decca Records less than six months after their formation. The group’s first single, “Steal Your Heart Away,” released in September of 1964, didn’t touch the British charts. But their second single, “Go Now,” released in November of 1964 — a cover of a nearly identical American single by R&B singer Bessie Banks, heavily featuring Laine’s mournful lead vocal — fulfilled every expectation and more, reaching number one in England and earning them a berth in some of the nation’s top performing venues (including the New Musical Express Poll Winners Concert, appearing with some of the top acts of the period); its number ten chart placement in America also earned them a place as a support act for the Beatles on one tour, and the release of a follow-up LP (Magnificent Moodies in England, Go Now in America) on both sides of the Atlantic.

It was coming up with a follow-up hit to “Go Now,” however, that proved their undoing. Despite their fledgling songwriting efforts and the access they had to American demos, this version of the Moody Blues never came up with another single success. By the end of the spring of 1965, the frustration was palpable within the band. The group decided to make their fourth single, “From the Bottom of My Heart,” an experiment with a different, much more subtly soulful sound, and it was one of the most extraordinary records of the entire British Invasion, with haunting performances all around. Unfortunately, the single only reached number 22 on the British charts following its release in May of 1965, and barely brushed the Top 100 in America. Ultimately, the grind of touring, coupled with the strains facing the group, became too much for Warwick, who exited in the spring of 1966; and by August of 1966 Laine had left as well. The group soldiered on, however, Warwick succeeded by John Lodge, an ex-bandmate of Ray Thomas, and in late 1966 singer/guitarist Justin Hayward joined.

For a time, they kept doing the same brand of music that the group had started with, but Hayward and Pinder were also writing different kinds of songs, reflecting somewhat more folk- and pop-oriented elements, that got out as singles, to little avail. At one point in 1966, the band decided to pull up stakes in England and start playing in Europe, where even a “has-been” British act could earn decent fees. And they began building a new act based on new material that was more in keeping with the slightly trippy, light psychedelic sounds that were becoming popular at the time. They were still critically short of money and prospects, however, when fate played a hand, in the form of a project initiated by Decca Records.

In contrast to America, where home stereo systems swept the country after 1958, in England, stereo was still not dominant, or even common, in most people’s homes — apart from classical listeners — in 1966. Decca had come up with “Deramic Stereo,” which offered a wide spread of sound, coupled with superbly clean and rich recording, and was trying to market it with an LP that would serve as a showcase, utilizing pop/rock done in a classical style. The Moody Blues, who owed the label unrecouped advances and recording session fees from their various failed post-“Go Now” releases, were picked for the proposed project, which was to be a rock version of Dvor’s New World Symphony. Instead, they were somehow able to convince the {@Decca producers involved that the proposed adaptation was wrongheaded, and to deliver something else; the producer, Tony Clarke, was impressed with some of the band’s own compositions, and with the approval of executive producer Hugh Mendl, and the cooperation of engineer Derek Varnals, the group effectively hijacked the project — instead of Dvor’s music, they arrived at the idea of an archetypal day’s cycle of living represented in rock songs set within an orchestral framework, utilizing conductor/arranger {$Peter Knight’s orchestrations to expand and bridge the songs. The result was the album Days of Future Passed.

The record’s mix of rock and classical sounds was new, and at first puzzled the record company, which didn’t know how to market it, but eventually the record was issued, first in England and later in America. It became a hit in England, propelled up the charts by the single “Nights in White Satin” (authored and sung by Hayward), which made the Top 20 in the U.K.; in America, the chosen single was another Hayward song, “Tuesday Afternoon.” All of it hooked directly into the aftermath of the Summer of Love, and the LP was — totally accidentally — timed perfectly to fall into the hands of listeners who were looking for an orchestral/psychedelic recording to follow works such as the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Better still, the band still had a significant backlog of excellent psychedelic-themed songs to draw on. Their debt wiped out and their music now in demand, they went to work with a follow-up record in short order and delivered In Search of the Lost Chord (1968), which was configured somewhat differently from its predecessor. Though Decca was ecstatic with the sales results of Days of Future Passed and the singles, and assigned Clarke and Varnals to work with them in the future, the label wasn’t willing to schedule full-blown orchestral sessions again. And having just come out of a financial hole, the group wasn’t about to go into debt again financing such a recording.

The solution to the problem of accompaniment came from Mike Pinder, and an organ-like device called a Mellotron. Using tape heads activated by the touch of keys, and tape loops comprised of the sounds of horns, strings, etc., the instrument generated an eerie, orchestra-like sound. Introduced at the start of the ’60s as a potential rival to the Hammond organ, the Mellotron had worked its way into rock music slowly, in acts such as the Graham Bond Organisation, and had emerged to some public prominence on Beatles’ records such as “Strawberry Fields Forever” and, more recently, “I Am the Walrus”; during that same year, in a similar supporting capacity, it would also turn up on the Rolling Stones’ Their Satanic Majesties Request. As it happened, Pinder not only knew how to play the Mellotron, but had also worked in the factory that built them, which enabled him over the years to re-engineer, modify, and customize the instruments to his specifications. (The resulting instruments were nicknamed “Pindertrons.”)

In Search of the Lost Chord (1968) put the Mellotron in the spotlight, and it quickly became a part of their signature sound. The album, sublimely beautiful and steeped in a strange mix of British whimsy (“Dr. Livingston I Presume”) and ornate, languid Eastern-oriented songs (“Visions of Paradise,” “Om”), also introduced one psychedelic-era anthem, “Legend of a Mind”; authored by Ray Thomas and utilizing the name of LSD guru Timothy Leary in its lyric and choruses, along with swooping cellos and lilting flute, it helped make the band an instant favorite among the late-’60s counterculture. (The group members have since admitted at various times that they were, as was the norm at the time, indulging in various hallucinogenic substances.) That album and its follow-up, 1969’s On the Threshold of a Dream, were magnificent achievements, utilizing their multi-instrumental skills and the full capability of the studio in overdubbing voices, instruments, etc. But in the process of making those two LPs, the group found that they’d painted themselves into a corner as performing musicians — thanks to overdubbing, those albums were essentially the work of 15 or 20 Moody Blues, not a quintet, and they were unable to re-create their sound properly in concert.

From their album To Our Children’s Children’s Children — which was also the first release of the group’s own newly founded label, Threshold Records — only one song, the guitar-driven “Gypsy,” ever worked on-stage. Beginning with A Question of Balance (1970), the group specifically recorded songs in arrangements that they could play in concert, stripping down their sound a bit by reducing their reliance on overdubbing and, in the process, toughening up their sound. They were able to do most of that album and their next record, Every Good Boy Deserves Favour, on-stage, with impressive results. By that time, all five members of the band were composing songs, and each had his own identity, Pinder the impassioned mystic, Lodge the rocker, Edge the poet, Thomas the playful mystic, and Hayward the romantic — all had contributed significantly to their repertoire, though Hayward tended to have the biggest share of the group’s singles, and his songs often occupied the lead-off spot on their LPs.

Meanwhile, a significant part of their audience didn’t think of the Moody Blues merely as musicians but, rather, as spiritual guides. John Lodge’s song “I’m Just a Singer (In a Rock & Roll Band)” was his answer to this phenomenon, renouncing the role that had been thrust upon the band — it was also an unusually hard-rocking number for the group, and was also a modest hit single. Ironically, in 1972, the group was suddenly competing with itself when “Nights in White Satin” charted again in America and England, selling far more than it had in 1967; that new round of single sales also resulted in Days of Future Passed selling anew by the tens of thousands.

In the midst of all of this activity, the members, finally slowing down and enjoying the fruits of their success, had reached an impasse. As they prepared to record their new album, Seventh Sojourn (1972), the strain of touring and recording steadily for five years had taken its toll. Good songs were becoming more difficult to deliver and record, and cutting that album had proved nearly impossible. The public never saw the problems, and its release earned them their best reviews to date and was accompanied by a major international tour, and the sales and attendance were huge. Once the tour was over, however, it was announced that the group was going on hiatus — they wouldn’t work together again for five years. Hayward and Lodge recorded a very successful duet album, Blue Jays (1975), and all five members did solo albums. All were released through Threshold, which was still distributed by English Decca (then called London Records in the United States), and Threshold even maintained a small catalog of other artists, including Trapeze and Providence, though they evidently missed their chance to sign a group that might well have eclipsed the Moody Blues musically, King Crimson. (Ironically, the latter also used the Mellotron as a central part of their sound, but in a totally different way, and were the only group ever to make more distinctive use of the instrument.)

The Moodies’ old records were strong enough, elicited enough positive memories, and picked up enough new listeners (even amid the punk and disco booms) that a double-LP retrospective (This Is the Moody Blues) sold extremely well, years after they’d stopped working together, as did a live/studio archival double LP (Caught Live + 5). By 1977, the members had decided to reunite — although all five participated in the resulting album, Octave (1978), there were numerous stresses during its recording, and Pinder was ultimately unhappy enough with the LP to decline to go on tour with the band. The reunion tour came off anyway, with ex-Yes keyboardist Patrick Moraz brought in to fill out the lineup, and the album topped the charts.

The group’s next record, Long Distance Voyager (1981), was even more popular, though by this time a schism was beginning to develop between the band and the critical community. The reviews from critics (who’d seldom been that enamored of the band even in its heyday) became ever more harsh, and although their hiatus had allowed the band to skip the punk era, they seemed just as out of step amid the MTV era and the ascendancy of acts such as Madonna, the Pretenders, the Police, et al. By 1981, they’d been tagged by most of the rock press with the label “dinosaurs,” seemingly awaiting extinction. There were still decent-sized hits, such as “Gemini Dream,” but the albums and a lot of the songwriting seemed increasingly to be a matter of their going through the motions of being a group — psychedelia had given way to what was, apart from the occasional Lodge or Hayward single, rather soulless pop/rock. There were OK records, and the concerts drew well, mostly for the older songs, but there was little urgency or very much memorable about the new material.

That all changed a bit when one of them finally delivered a song so good that in its mere existence it begged to be recorded — the Hayward-authored single “Your Wildest Dreams” (1986), an almost perfect successor to “Nights in White Satin” mixing romance, passion, and feelings of nostalgia with a melody that was gorgeous and instantly memorable (and with a great beat). The single — along with its accompanying album, which was otherwise a much blander affair — approached the top of the charts. They were boosted up there by a superb promotional video (featuring the Mood Six as the younger Moody Blues) that suddenly gave the group at least a little contemporary pop/rock credibility. The follow-up, “I Know You’re Out There Somewhere,” was a lesser but still impressive commercial success, with an even better secondary melodic theme, and the two combined gave them an essential and memorable pair of mid-decade hits, boosting their concert attendance back up and shoring up their contemporary songbag.

By the end of the ’80s, however, they were again perceived as a nostalgia act, albeit one with a huge audience — a bit like the Grateful Dead without the critical respect or veneration. By that time, Moraz was gone and the core group was reduced to a quartet, with salaried keyboard players augmenting their work (along with a second drummer to back up Edge). They had also begun attracting fans by the tens of thousands to a new series of concerts, in which — for the first time — they performed with orchestras and, thus, could do their most elaborately produced songs on-stage. In 1994, a four-CD set devoted to their work, entitled Time Traveller, was released. By that time, their new albums were barely charting, and seldom attracting any reviews, but their catalog was among the best-selling parts of the Polygram library.

A new studio effort, Strange Times, followed in 1999 and the live (at the Royal Albert Hall) Hall of Fame was issued a year later, but it was the 1997 upgrades of their original seven albums, from Days of Future Passed to Seventh Sojourn, that attracted far more attention from the public. In 2003, Ray Thomas retired, and the Moody Blues carried on as a core trio of Hayward, Lodge, and Edge. They were still going strong as a touring band in 2009, the same period in which their live performance from the 1970 Isle of Wight Festival was released as a CD and a DVD. That same year, Hayward’s “Tuesday Afternoon” began turning up as an accompaniment to commercials for Visa. In 2013, the Moody Blues were the subject of a four-disc box retrospective from Universal entitled Timeless Flight. ~ Bruce Eder, Rovi